Active prosthesis(1) and handisport performance(2)

The global edition of the Cybathlon 2020 kicked off online on 13 November. Initially scheduled for May 2020 in Zurich, the competition was held in a 100% local and digital format due to the current health context. This decentralised organisation enabled each of the participating teams, made up of pilots and engineers, to compete in one of the six disciplines on offer: Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) race, Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) bike race, Powered Arm Prosthesis Race (ARM), Powered Leg Prosthesis Race (LEG), Powered Exoskeleton Race (EXO) and Powered Wheelchair Race (WHL).

A first participation for the ISIR Smart ArM team (Sorbonne University/CNRS/INSERM)

The competing teams recorded their runs under the watchful eye of external referees recruited locally and officials by videoconference from Switzerland and followed the broadcasting of the event and the announcement of the podiums from their respective countries. Represented by the competitor and former Paralympic athlete Christophe Huchet, the SAM team placed 10th in the ARM discipline. The athlete, the only competitor in the race who was born without an elbow and forearm, faced the challenge of piloting a sophisticated prosthesis developed at the ISIR and designed especially for him. Thanks to its commitment and the expert support of its teammates, the SAM team was able to stay the course and meet a requirement that is increasingly present in the world of robotics: to take a giant step towards integrating the human being in the co-design of active prostheses based on its feedback and considering him/her as a stakeholder in any future progress.

Combined events: towards skilful two-handed interaction

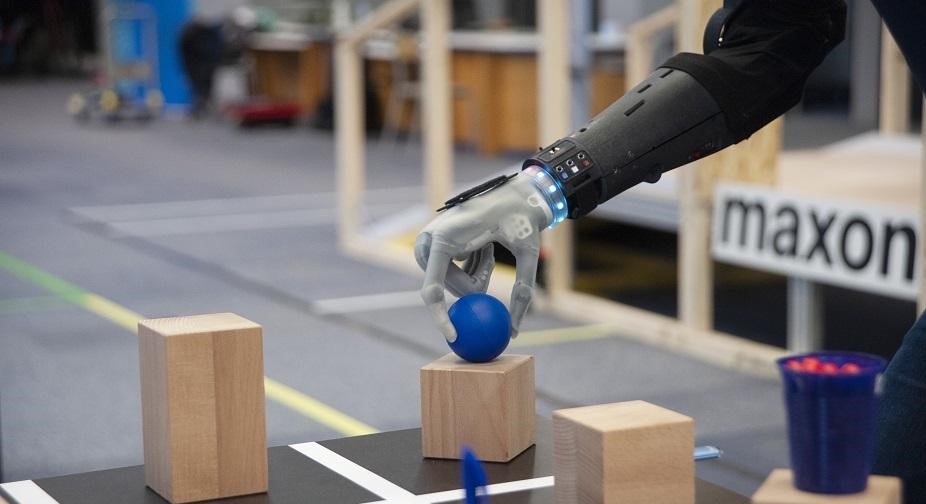

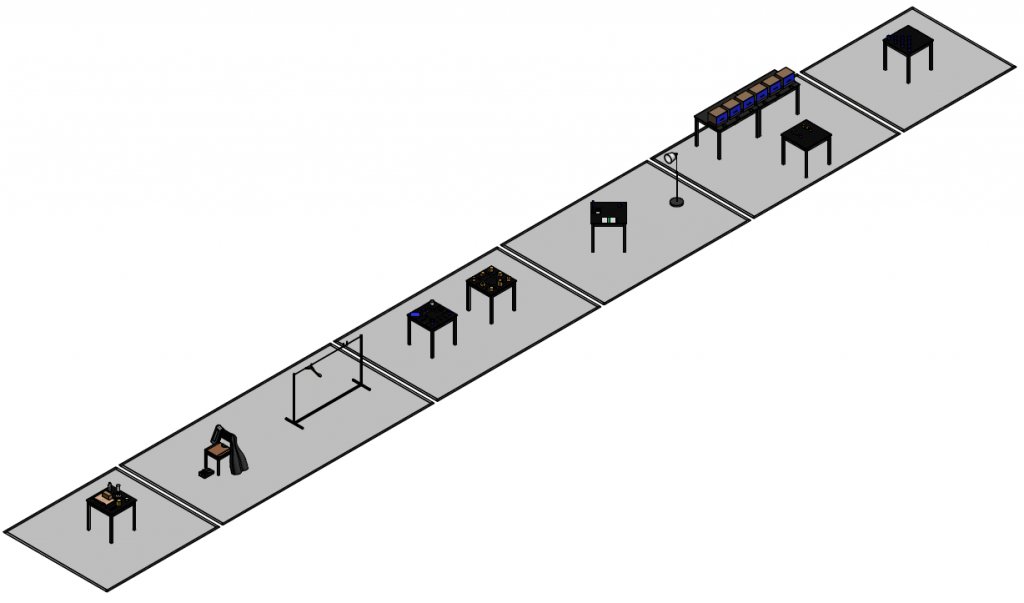

With a mentality of steel, the competitors in the ARM discipline accomplished tasks of everyday life within the time limit of the race. To do so, the drivers had to use kitchen utensils, get dressed, hang out clothes, move objects of different shapes and sizes, change light bulbs, identify objects by touch and stack cups to build a pyramid, all in record time. The aim is to improve the speed and precision of the gesture.

Man learning outside the “capability” model(3)

Technical dexterity is at the heart of the search for increased efficiency and is necessary for any wearer wishing to increase their means of interaction with their world. The “man-machine” assembly today makes it possible to underline the importance of the learning process in the appropriation of prosthetic appliances. The events of the six Cybathlon disciplines combined make it possible to tie in with the dream of Olympus and to acclimatise it to a context where robotic technologies and movement sciences are possible matrices for questioning the limits of the human body while respecting its diversity and the multiplicity of the stories that animate it.

Reinventing the sporting gesture

By broadening the scope of the sports movement, the competitive gesture now takes into account the obstacles that present themselves to any person with a motor deficit. In this sense, the Cybathlon competition marks a real turning point towards a new sporting model. The events are designed to reflect the level of mental and physical stamina that the prosthesis operator faces when performing everyday tasks. This event, which could become a key date in the international competition calendar, brings together teams from all over the world and aims to create synergies between the different carriers of these robotic technologies and the scientific experts in the field. In this sense, the “Man-Machine” assembly will continue to discover itself by emphasising the importance of the role of the human being in all future research.

If the search for greater efficiency is at the heart of this learning process, the same applies to questions of fatigue, happiness, fulfilment and democratisation of access to these prosthetic devices, themes that interest our researchers in a context that combines science and disability studies4. While we await the next Cybathlon, which will take place in 4 years, the eyes of all those who are passionate about surpassing themselves remain focused on the new disciplines that will emerge.

(1) These are distinguished from passive prostheses used in the context of disabled sport competitions.

(2) The word handicap comes from the English expression “hand in cap” or “hand in the hat”, a reference to a lottery game or exchange of objects. The first use of the term in a sporting context dates back to the 18th century. Handicap referred to a disadvantage imposed on a skilled competitor at a higher sporting level in order to ensure an equal chance of winning for other competitors (e.g. imposing an extra weight or distance in a horse race).

(3) Translated from the English, ableism or disablism, discrimination against persons with disabilities. See Stanford Encyclopeadia of Philosophy, Critical disabilité theory.

(4) See Manifesto of the Collective Body and Prosthesis.

>> Watch the CNRS report <<

>> Review the race of the SAM team <<

Source : Sorbonne University